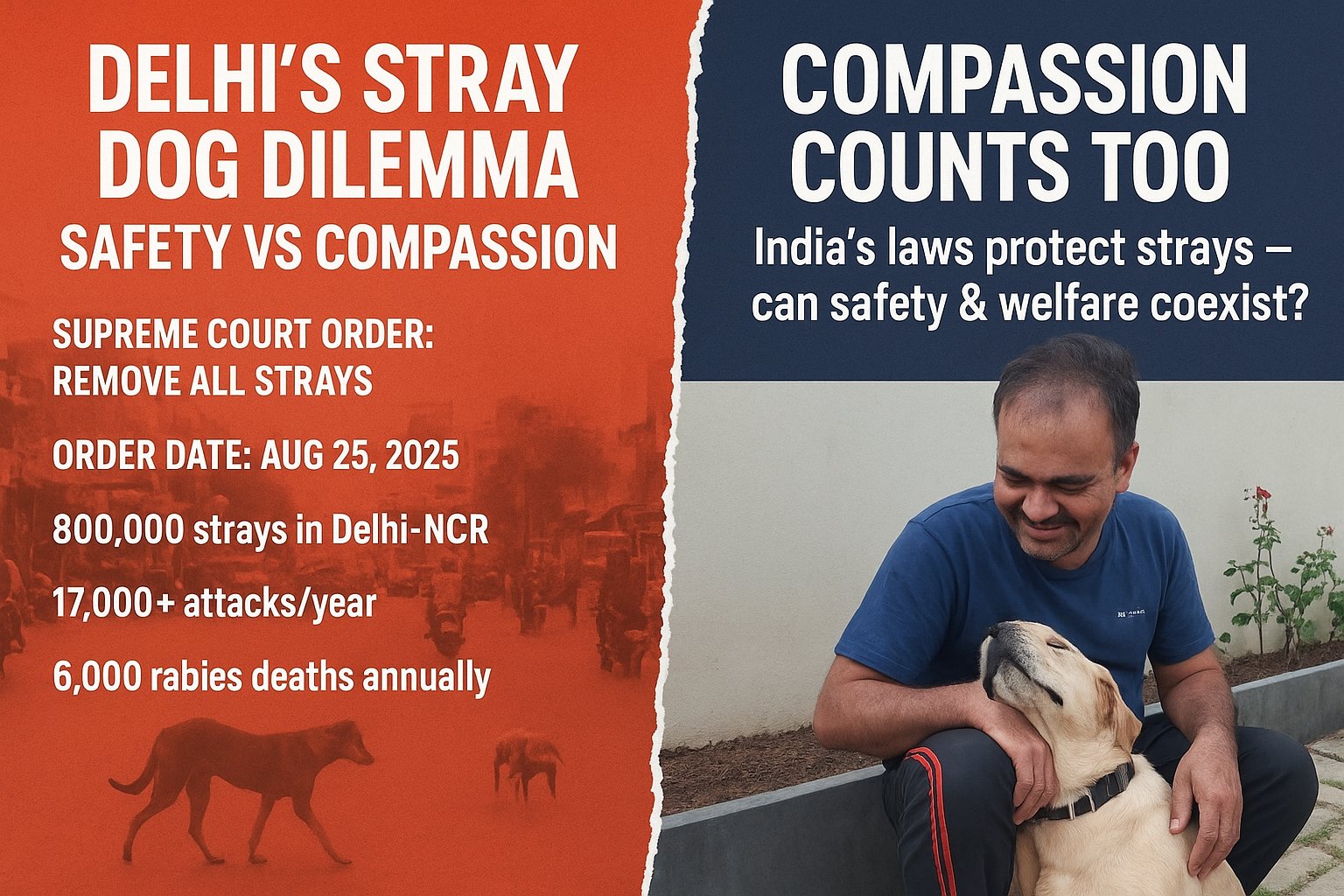

The Supreme Court of India recently issued a hard hitting order that could fundamentally change the way India’s capital deals with its stray dog population. In a move aimed squarely at public safety, the Court directed that all stray dogs in NCR be removed from the streets and relocated to designated shelters.

The order leaves little room for ambiguity, it is intended to protect the public from rising incidents of dog bites and rabies. Authorities were told to begin roundups immediately, focusing on high risk localities first. The Court even went as far as warning that anyone interfering with the process including animal activists would face contempt charges.

The reaction was swift and deeply divided. Supporters argued that the measure was overdue, citing high profile cases of stray dog attacks, some resulting in fatalities. They argue that the streets are for people first, and allowing aggressive dogs to roam unchecked is a public health hazard. Critics, however, say the Court’s directive is hasty, impractical, and based on unrealistic timelines. They point out that the logistical demands of sheltering hundreds of thousands of animals are staggering, and question whether the move is legally consistent with India’s existing animal welfare laws.

The Scale of the Problem

To understand the magnitude of the challenge, the numbers speak for themselves. Delhi NCR alone is estimated to have about 800,000 stray dogs. Across India, the number exceeds 50 million.

Every minute, five people are bitten by dogs in India that’s nearly three million bites every year. Of these, around 6,000 people die annually from rabies, a disease almost always transmitted through dog bites.

While alarming, these numbers also need context. India loses 55,000 lives each year to snake bites, 700,000 to mosquito borne diseases like malaria and dengue, and more than 2,000 to wild animal attacks by elephants, tigers, and leopards. Dog bites are a serious problem but they are part of a much larger spectrum of human animal conflicts in India.

India’s animal welfare laws ban the culling of stray dogs, and harming them is a punishable offence. The current official strategy the Animal Birth Control programme is designed to sterilise and vaccinate strays, then return them to their original territories. The idea is to gradually control the population over time while reducing the spread of rabies.

Why the Court’s Order is So Difficult to Implement ?

The Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD) currently operates 20 ABC centres in partnership with NGOs. These facilities are meant for short term holding, usually keeping dogs for about 10 days post sterilisation before releasing them back.

But the Court’s order demands permanent relocation to shelters a scale for which Delhi is nowhere near prepared.

Feeding costs alone would cripple the MCD, feeding close to a million dogs would cost lakhs or crores daily. Infrastructure needs are staggering as well. Humane housing for even half the stray population would require upto 2,000 separate centres spread across hundreds of acres. Dogs can’t be crammed into overcrowded sheds they will fight, spread disease, and die in large numbers. Manpower availability is scarce. Hundreds of trained handlers, animal catchers, veterinarians, ambulances, and quarantine units would be required. The city’s 77 veterinary hospitals are already understaffed and underequipped.

Moreover, forcibly removing dogs from streets is bound to provoke an emotional backlash. In many Delhi colonies, residents feed and care for local strays, seeing them as part of the community. For these people, the Court’s order is not just an administrative move it’s the removal of animals they consider family.

A Personal Viewpoint

I find it hard to label all stray dogs as aggressive. My perspective is shaped by personal experience.

I grew up in a household that had pet dogs for over two decades. Our first was a street rescue I picked up as a schoolkid. He was fiercely loyal, protective, and deeply affectionate. The second was a mix of a dachshund and a local Indian dog again, hardy and loving. Later, we had a Doberman, who was wonderful but sadly died young of canine distemper.

From a purely practical standpoint, the street dogs were easier to maintain. They were hardy, largely immune to common diseases, and adaptable. The Doberman, by contrast, needed far more care and was vulnerable to illnesses.

When I lived in Delhi for over 20 years, often returning home well past 10 p.m., I never once faced an attack. That may have been luck, or it may reflect the fact that dogs tend to leave you alone unless provoked. Still, I acknowledge that attacks do happen and for those affected, the trauma is real.

Why Do Stray Dogs Become Aggressive?

Several factors contribute to aggression in strays:

1. Strays thrive on easily available food. Poorly managed waste, especially meat scraps from hotels and households, creates a steady food supply. In states like Kerala, where non vegetarian foo consumption is high and waste management is notoriously poor, dogs grow larger, stronger, and more territorial.

2. The extremely unfortunate habit of abandoning pet dogs. Abandoning German Shepherds, Dobermans, rottweilers & other potentially aggressive breeds leads them to mix and cross breed with local dogs . Abandoned dogs face hunger, illness, injury, and in many cases, death. They are left confused, frightened, and vulnerable, with little hope of survival without intervention.

3. Negative Human Interactions. Abuse, neglect, and mistreatment can make dogs fearful and defensive, sometimes leading to unprovoked aggression.

4. Though well intentioned feeding stray dogs in one area can attract more dogs, leading to competition for food, territory disputes, and increased aggression.

Lessons from Other Countries

Other nations have tackled stray dog populations with mixed strategies. Turkey, for example, has widespread sterilisation and vaccination programmes but still allows strays to roam, often cared for by local communities. In contrast, Singapore’s aggressive animal control policies ensure very few strays remain, but such measures are backed by strong infrastructure and consistent funding something Indian municipalities lack.

The common thread in successful cases is longterm planning, community involvement, and adequate resources none of which can be created overnight.

The Way Forward

The Supreme Court’s intention to protect public safety is valid. But the execution plan, as it stands, is unrealistic. Removing every stray dog from Delhi’s streets within a matter of weeks is simply not possible.

A more practical roadmap could involve:

Scaling up sterilisation and vaccination with significant central and state funding.

Improving waste management to cut off food supply in public spaces, naturally reducing stray populations over time.

Partnering with animal welfare groups like PFA and AWBI to leverage existing networks and expertise.

Public awareness campaigns to discourage abandonment of pets and promote responsible ownership.

Developing regional shelters with humane capacity, built gradually over years rather than rushed in weeks.

India’s stray dog challenge is both a public health issue and a social one. A humane, structured, and community driven approach is the only sustainable way forward. Quick fixes, however well intentioned, are destined to fail.

In the end, we must balance compassion for animals with the safety of citizens. Human–animal conflict is real, and it must be addressed. But if the Court’s goal is to find a permanent solution, it will need patience, planning, and practical timelines not just sweeping orders.